Your Phone is a Fake Berry Bush: Why You Keep Scrolling

I’m on the couch, watching a show I’m genuinely enjoying. Good plot, good acting, no complaints. And then I notice my phone is in my hand. I’m looking at it. I don’t remember picking it up.

Here’s the strange part: I don’t actually want to check anything. No message I’m waiting for, no notification that pulled me in. I just… opened it. Automatically. Like a reflex. I catch myself staring at the home screen, thumb hovering, with no idea what I intended to do.

It’s even weirder when you see it from outside. I’ll be talking with someone, mid-sentence, and they pull out their phone and start scrolling. They don’t seem to notice they’ve done it. I don’t think they’re being rude on purpose. It’s more like their hand just… moved.

I got curious about why this happens. I dug into the research, and I have good news and bad news.

The bad news: you’re not going to willpower your way out of this. The systems driving that behavior are ancient, powerful, and mostly invisible to conscious thought.

The good news: once you understand why your brain does this, you can stop blaming yourself and start designing around it. This isn’t a character flaw. It’s evolutionary biology colliding with teams of engineers who’ve figured out exactly how to exploit it.

But I also wonder: if these systems are this powerful, could they be used for good? Could I get addicted to deep work, or learning, or working out, the way I’m addicted to my phone?

Part 1: The Exploitation Playbook

Open TikTok. Swipe. Meh. Swipe. Meh. Swipe. Okay, that was kind of funny. Swipe. Meh. Swipe. Meh. Swipe. Meh. Swipe. Oh wow, that’s actually amazing.

You just experienced the reward pattern that makes slot machines work. And it’s not an accident.

Consider what TikTok is actually doing. Most videos are mediocre, some are good, and occasionally one is perfect for you. You can’t predict which swipe will pay off: variable rewards. The next video is one thumb movement away, no searching, no deciding, no effort: no friction. The feed never ends, so there’s no natural place to quit: no stopping point. And that video that was almost funny, that post that was almost interesting? Each one feels like progress toward the jackpot: near-misses.

This isn’t just TikTok. Instagram Reels, YouTube Shorts, Twitter feeds, Tinder: same formula. Dating apps turn human connection into a swipe-based slot machine. Even browsing Netflix or YouTube’s homepage is a kind of foraging through mediocre thumbnails hoping to strike gold. The pattern is everywhere once you see it.

Why does it work so well? The answer starts with a psychologist, some pigeons, and casinos that figured out the formula before the science existed.

Part 2: The Science of Why It Works

Skinner’s Pigeons

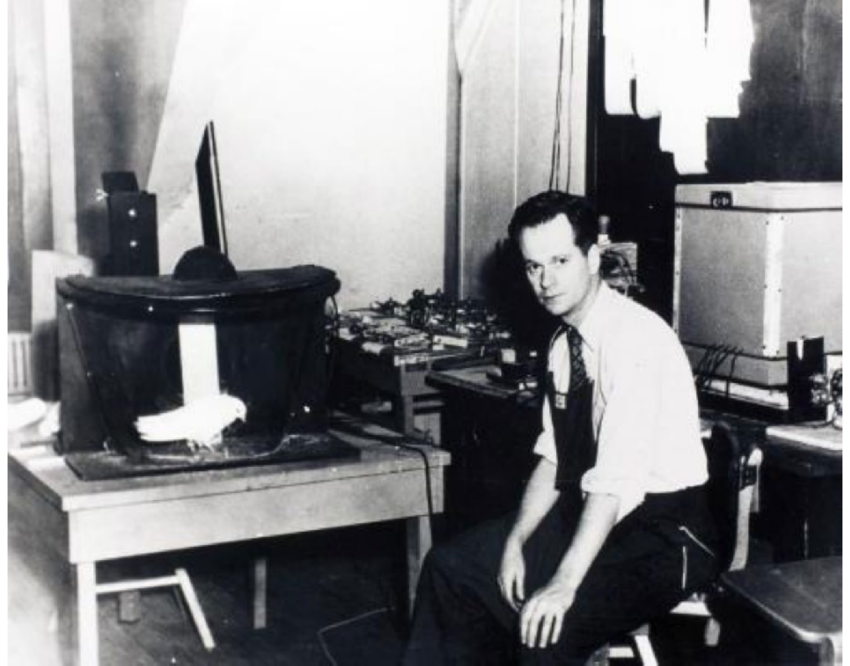

Photo courtesy of the B.F. Skinner Foundation

Photo courtesy of the B.F. Skinner Foundation

In the 1950s, B.F. Skinner was studying how animals learn. He put pigeons in boxes with a lever they could peck. Peck the lever, get food.

As Skinner later told it, he stumbled onto something unexpected while running low on food pellets. When rewards came predictably (every peck, or every tenth peck) the pigeons behaved predictably too. They’d peck, eat, take breaks. Sensible birds.

But when rewards came randomly? Sometimes on the third peck, sometimes on the twentieth, sometimes twice in a row? The pigeons became obsessive, pecking with manic persistence, far more than under any predictable schedule. Skinner had discovered variable ratio reinforcement: random rewards for repeated actions.

In 1957, Skinner and his colleague C.B. Ferster published Schedules of Reinforcement, which formalized these findings through rigorous experimentation. But when Skinner wrote about gambling in 1953, he noted something interesting: “the efficacy of such schedules in generating high rates has long been known to the proprietors of gambling establishments.”

The casinos had figured it out empirically before the science caught up.

How Casinos Engineered Addiction

How did casino owners discover the optimal formula for addiction without running controlled experiments on pigeons? To answer that, we need to go back before slot machines existed at all.

In 1891, Sittman and Pitt of Brooklyn, New York built a gambling machine that used five spinning drums, each holding ten playing cards. It was essentially mechanized poker. Players would insert a nickel, pull a lever, and hope the drums landed on a good poker hand. There was no automatic payout; you’d show your result to the bartender and collect your prize (usually free drinks or cigars). The machine was wildly popular. Within a few years, nearly every bar in New York had one.

But notice what this machine didn’t have: drama. All five drums stopped at roughly the same time. You either got a good hand or you didn’t. There was no “almost.”

A few years later, Charles Fey, a Bavarian immigrant working as a mechanic in San Francisco, saw an opportunity. He’d been tinkering with coin-operated machines for years, and in the late 1890s he built something different: the Liberty Bell.

Fey’s design made three changes. First, he replaced the five poker drums with three simpler reels, each showing just five symbols: horseshoes, diamonds, spades, hearts, and liberty bells. Fewer combinations meant automatic payouts became possible.

Second, and more importantly, he made the reels stop sequentially. The first reel lands: cherry. The second reel lands: cherry. The third reel is still spinning… then it lands: lemon. You were so close.

This delay was the innovation that mattered. Fey had accidentally built the near-miss into the machine’s physical structure. Earlier color-wheel machines revealed results all at once, so you could calculate your odds from what you saw. With three sequential reels showing just a fraction of the thousand possible combinations (10 × 10 × 10), players had no way to calculate the payout percentage. More importantly, the sequential stopping created suspense and that feeling of “almost winning” the poker machines lacked.

The Liberty Bell was enormously successful. Because gambling was illegal in California, Fey couldn’t patent his device, and competitors immediately began copying it. Within a decade, slot machines were everywhere.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

But the real engineering came later. In the early 1980s, when computerized slots began replacing mechanical reels, designers gained precise control over probabilities. They developed a technique called “virtual reel mapping,” where the physical symbols you see spinning don’t correspond to the actual odds. A jackpot symbol might appear on the physical reel as often as any other, but in the computer’s virtual reel (which determines outcomes), it appears far less frequently.

More insidiously, designers began using “clustering,” deliberately placing blank stops next to jackpot symbols on the virtual reel. The result: when you lose, you frequently see the jackpot symbol just above or just below the payline. A near-miss. Your brain registers it as “almost,” even though the computer had already determined you’d lost the instant you pulled the lever.

This wasn’t subtle. In 1988, a case came before the Nevada Gaming Commission challenging one manufacturer’s algorithms for generating an artificially high rate of near-misses. The commission ruled that certain techniques were “unacceptable,” but notably, virtual reel mapping that creates near-misses above and below the payline remains legal to this day.

The casinos didn’t need Skinner’s research to design addictive machines. They had something better: direct feedback on what keeps people pulling the lever, refined over a century. What Fey stumbled onto with sequential reels, modern designers have turned into a science.

The Near-Miss Trick

In 2009, Luke Clark and colleagues at Cambridge put volunteers in brain scanners and had them play slot machines. When someone won, their reward circuits lit up, specifically the ventral striatum, the same region that responds to food and sex. When someone almost won (cherry-cherry-lemon), their reward circuits also lit up. Almost as much as for a real win.

Your brain treats “I almost got it!” as genuine progress. This would be sensible if slot machines were skill-based games where getting close meant you were improving. But they’re not. The outcome is determined the instant you pull the lever. Cherry-cherry-lemon tells you nothing about what the next spin will bring.

Yet your brain thinks: “I was so close! Next time!”

A 2001 study by psychologists Jeffrey Kassinove and Mitchell Schare tested near-miss rates of 15%, 30%, and 45% on participants playing a simulated slot machine. The 30% condition produced the greatest persistence, with participants continuing to play significantly longer than in either the 15% or 45% conditions. Modern slot machines are engineered with this in mind.

Now think about your feed. That video that was almost funny. That profile on Tinder that was almost your type. That thread that was almost insightful. Each near-miss keeps you swiping, because your brain registers it as progress toward the jackpot.

Schultz’s Monkeys

Skinner showed what kept animals hooked. But it took another few decades to understand how the brain actually processes these rewards.

In the 1990s, Wolfram Schultz at Cambridge was studying monkeys. He wanted to understand dopamine, the neurotransmitter everyone assumed was the “pleasure chemical.” The thinking: you eat something delicious, dopamine releases, you feel pleasure. Simple.

Schultz designed an experiment to test this. A monkey reaches into a box, finds a treat. He recorded what the dopamine neurons were doing. At first, the neurons fired when the monkey got the treat. If dopamine equals pleasure, this confirmed the theory.

But then he noticed something that didn’t fit. After the monkey learned that the box always contained a treat, the dopamine response shifted. Now the neurons fired when the monkey saw the box, not when it got the treat. The actual reward barely registered anymore.

And when the monkey expected a treat but didn’t get one? The dopamine neurons went below baseline, a negative signal. When it expected nothing but got a treat anyway? A huge spike.

Schultz realized he wasn’t looking at a pleasure signal. He was looking at a prediction error signal. In a 1997 paper that changed the field, he showed that dopamine tracks the gap between what you expected and what you got:

- Better than expected → dopamine spike

- As expected → nothing

- Worse than expected → dopamine dip

This explains why your tenth bite of cake is less exciting than your first, even though the taste is identical. The first bite exceeded prediction. The tenth matched it. Same cake, different signal.

And it explains why variable rewards are so compelling. When you can’t predict whether the next swipe will be good or bad, every swipe generates potential prediction error. Your dopamine system stays engaged, perpetually anticipating the possibility of surprise.

Berridge’s Rats

Around the same time Schultz was studying monkeys, Kent Berridge at the University of Michigan was studying rats and sweet tastes. Normal rats, when you give them sugar water, make a characteristic facial expression, a “yum” face that looks remarkably similar across mammals, including human babies.

Berridge tried something extreme: he destroyed most of the dopamine system in these rats. If dopamine was the pleasure chemical, these rats shouldn’t enjoy sugar anymore.

But they still liked sugar. When it touched their tongues, they made the same “yum” face. The pleasure was intact. What was gone was any motivation to seek it out. They’d walk right past a pile of sugar and starve to death. If you put sugar in their mouths, they’d happily consume it. They just wouldn’t go get it.

Berridge had discovered that wanting and liking are separate systems. Dopamine doesn’t make you enjoy things. It makes you want things, what Berridge calls “incentive salience,” the feeling that something is worth pursuing. Actual enjoyment comes from different, smaller neural circuits involving opioids.

This separation is what makes certain behaviors so insidious. You can want something intensely while barely enjoying it when you get it.

Think about checking your phone. You feel a pull to check it. That’s wanting, dopamine signaling that something potentially rewarding might be there. You check. Mostly nothing interesting. You don’t particularly enjoy the experience. But a few minutes later, you feel the pull again. The wanting returns, even though the liking never showed up.

Or think about eating chips from a bag. You’re not savoring each chip. They’re fine. But you keep reaching for the next one, and the next one, and suddenly the bag is empty and you feel vaguely sick. The wanting drove the behavior. The liking was barely involved.

Berridge has described addiction as “a starved want in an unstarved brain,” the wanting mechanism running at full intensity while the liking mechanism provides no corresponding satisfaction. App designers don’t need you to enjoy their product. They just need you to keep wanting to check it.

The Foraging Brain

Why does your brain fall for this? Because these systems weren’t designed for the modern world. They were designed for finding food when you don’t know where it is.

The idea that our dopamine systems are essentially foraging circuits comes from optimal foraging theory, developed by ecologists Eric Charnov and Robert MacArthur in the 1960s. Researchers at Xerox PARC later applied this framework to human information-seeking behavior. And ethologist Niko Tinbergen’s work on “supernormal stimuli” helps explain why digital environments are so compelling: artificially exaggerated triggers hijack instincts more effectively than the natural stimuli those instincts evolved for.

Imagine you’re a proto-human on the African savanna. Food is scattered unpredictably across the landscape. Some bushes have berries, most don’t. Some areas have tubers, but you have to dig to find out. Some paths lead to watering holes where you might catch prey, or you might waste hours finding nothing.

Most of your attempts fail. And they have to fail. If food were easy to find, it would already be gone. Your survival depends on persistence through endless disappointment.

The dopamine system evolved to solve this problem. It rewards the search, not just the find. It makes the possibility of finding something almost as motivating as actually finding it. Your ancestors who kept exploring (one more bush, one more trail, one more dig) occasionally hit jackpots: a carcass, a honeycomb, a patch of ripe fruit. Those who gave up too easily starved.

But there’s a second adaptation that’s crucial to understanding why these systems are so exploitable. If every failed attempt felt as bad as a successful find felt good, you’d be too demoralized to continue after three empty bushes. So the brain evolved an asymmetry: wins register strongly, losses barely register at all.

Finding food creates an intense, memorable spike. Not finding food is just… neutral. Not painful. Just nothing. You shrug it off and keep searching.

This asymmetry is exactly what gambling exploits. You lose ten times, and each loss barely registers. Then you win once, and the spike feels significant. Your brain does bad accounting: the one win looms larger than the ten losses. You keep playing.

These systems are ancient. Dopamine-based reward circuits aren’t unique to humans; they exist in insects, fish, even worms. When you feel the compulsive urge to check your phone, you’re fighting hundreds of millions of years of optimization.

But the foraging environment had built-in limits. You had to walk miles. You could only carry so much back to camp. You could only eat so much before you were full. The search eventually ended.

Modern technology has removed all these limits. “Rewards” are infinite. Effort is negligible, just moving your thumb. There’s no upper bound, no natural stopping point. Your brain cannot tell the difference between “I found food that will keep my family alive” and “I found an entertaining video.” Both trigger the same ancient system. Both feel like something. One matters. The other just consumed twenty minutes of your life.

Part 3: What’s New

Skinner’s research is from the 1950s. Schultz’s key papers came out in 1997. You might wonder: have we learned anything new? We have, and it makes the picture more concerning.

TikTok’s algorithm isn’t Skinner’s random reinforcement schedule, and it’s not a slot machine’s fixed probabilities. It’s something more sophisticated: the slot machine is learning you.

Classic variable reinforcement is random. The pigeon gets food on an unpredictable schedule, but the schedule isn’t personalized. A slot machine pays out based on fixed probabilities that apply to everyone equally.

TikTok’s For You page is different. It’s watching which videos make you pause, which ones you watch to the end, which ones you rewatch, which ones you skip past immediately. It’s building a model of your specific dopamine triggers and then optimizing for them. This is variable rewards calibrated to your prediction error system.

This is why people describe the For You page as eerily accurate, like the app knows them better than they know themselves. It’s not just showing you random content hoping something lands. It’s testing, learning, and refining what works for you specifically.

Research on TikTok has identified something called the “flow experience,” a state of absorption where you lose track of time and become fully immersed in the content stream. A 2024 study found that the key predictor of problematic use isn’t just variable rewards; it’s this trance-like concentration where minutes slip into hours without awareness. Users consistently underestimate time spent on TikTok more than on other platforms.

This isn’t academic speculation anymore. In October 2024, thirteen U.S. states and D.C. sued TikTok, alleging that its algorithm is “designed to promote excessive, compulsive, and addictive use” in children. Whether or not the case succeeds, the fact that it exists signals something: the mechanisms we’ve been discussing have moved from psychology journals into courtrooms.

Part 4: Breaking Free

So what do you do with this knowledge?

The first thing to understand: willpower is not the answer. You’re not going to think your way out of systems that operate below conscious awareness and have been optimized for hundreds of millions of years.

But you can change the environment.

Understanding Your Triggers

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) helps people identify the thoughts and situations that trigger problematic behaviors. Rather than suppressing urges through willpower, CBT focuses on noticing patterns: what happens right before the behavior? What internal state are you in? What are you trying to avoid or achieve?

In trials with smartphone-addicted adolescents, 12-week CBT programs significantly reduced addiction scores. The most helpful module, according to participants, was called “Recognize the Triggers,” which taught people to notice why they were reaching for their phone in the first place.

The insight is that phone checking isn’t random. It’s triggered by specific internal states: boredom, loneliness, anxiety, the desire to escape an uncomfortable task, the need for stimulation. If you can notice why you’re reaching for the phone, you create a moment of choice that wasn’t there before.

Some questions to ask yourself in that moment: Am I feeling bored? What am I avoiding? Am I feeling lonely? What connection am I actually seeking? Am I feeling anxious? What would actually address the anxiety? And perhaps most useful, given what we know about wanting versus liking: will I actually enjoy this, or am I just responding to a pull?

That last question is worth developing into a practice. Before you check your phone, predict: “Will I feel better after 10 minutes of scrolling?” Then afterward, notice whether your prediction was accurate. Building this awareness helps reveal the gap between the pull and the payoff, the wanting that persists even when liking never shows up.

Environmental Design

The more effective approach is changing the environment so the behavior becomes harder in the first place. You won’t out-think systems optimized for millions of years. But you can redesign choice architecture so checking your phone requires more effort than not checking it.

The simplest intervention: turn off notifications. Every notification is a trigger, every buzz is your phone asking for attention. Most apps default to aggressive notification settings because their metric is engagement, not your wellbeing. Turn off notifications for everything except calls and messages from actual humans, and you’ve eliminated hundreds of daily triggers.

The next step is removing apps from your home screen. If you have to search for an app to open it, you’ve added a few seconds of friction. That small delay creates a moment where you can ask “Do I actually want to do this?” Having Instagram’s icon staring at you every time you unlock your phone is a cue that triggers wanting. Remove the cue and you remove the trigger.

For deeper focus, put your phone in another room entirely. A 2017 study from UT Austin found that participants with their phones in another room significantly outperformed those with phones on the desk, even when the phones were face-down and silent. Just having the phone nearby seemed to occupy cognitive resources. Part of your brain was dedicated to not checking it, and that effort cost something. (A 2024 meta-analysis of 33 studies found smaller effects than the original study, suggesting this may vary by individual, but even a small effect compounds over time.)

A more aggressive intervention is grayscale mode. A 2024 study by Dekker and Baumgartner found that participants used their phones about 20 minutes less per day with grayscale displays. The mechanism is simple: colorful visuals trigger dopamine responses. App icons and notification badges use bright, saturated colors specifically because those colors grab attention. Remove the colors, and the phone becomes less visually compelling. Some users find grayscale hard to maintain long-term, but even using it intermittently (say, after 9pm) can help.

Other friction techniques include logging out of apps after each use (having to re-enter a password creates a pause that’s often enough to break the automatic behavior) and using browser versions instead of apps (the mobile web version of Twitter or Instagram is clunkier, slower, and less optimized for addiction, which is a feature, not a bug).

For some people, friction isn’t enough. Deleting the apps entirely is the only thing that works. If you find yourself reinstalling apps you’ve deleted, that’s useful information about how strong the pull is.

Making Losses Visible

Remember the foraging asymmetry: wins register strongly, losses fade. One way to counter this is to make the losses visible.

Screen time tracking does this automatically. Seeing “4 hours 23 minutes on TikTok” at the end of the day is information your brain would otherwise ignore. You might not remember the scrolling (each mediocre video faded from memory as soon as it passed) but you’ll notice the number.

Some people find journaling useful: after a scrolling session, write down what you actually got from it. Often the answer is “nothing” or “I feel worse.” Recording this counters the brain’s tendency to remember the occasional good video and forget the hundred forgettable ones.

Part 5: Using It For Good

If these mechanisms are so powerful, can they be used for good? Can you get addicted to working out, or to learning, or to doing deep work? Imagine if school were as compelling as TikTok. Imagine if you felt the same pull toward your workout that you feel toward your phone.

People have tried. The results are instructive.

What Duolingo Got Wrong

Duolingo is the most famous attempt at making learning addictive. If you haven’t used it: the app teaches languages through short exercises, mostly translation. Complete a lesson and earn XP. The amount varies unpredictably: bonus XP for a “perfect lesson” or daily challenges. Leaderboards let you compete against strangers for weekly rankings, and streaks track consecutive days practiced. Miss a day and the streak resets.

The notifications are remarkably persistent. Duo, the green owl mascot, sends messages like “These reminders don’t seem to be working. We’ll stop sending them for now.” (guilt trip) or “You made Duo sad” with an image of the owl looking dejected. According to Duolingo’s own reports, passive-aggressive notifications outperform friendly ones.

And it works, for engagement. Duolingo’s 2024 investor reports show daily active users at 34% of monthly active users, with over 10 million maintaining year-long streaks.

But many people use Duolingo for years and still can’t hold a conversation. Applied linguist Matt Kessler has studied this gap: Duolingo is effective for receptive skills (reading, listening, vocabulary) but users consistently struggle with productive skills like speaking and writing. One user described arriving in Sweden after hundreds of hours on Duolingo, able to read magazine articles but unable to order a coffee.

The problem isn’t just gamification. It’s that Duolingo’s core learning method (translation between languages) trains you to convert rather than to think in the new language. And because streaks reward showing up rather than improving, users optimize for the wrong thing. Someone with a 500-day streak might spend their daily five minutes on an easy lesson they’ve already mastered, just to preserve the streak, when watching a three-minute video in the target language would be more useful.

Duolingo made people addicted to using the app, not to learning. The engagement and the outcome became decoupled.

What About “TikTok for Learning”?

You’ve probably seen ads for apps like Headway, Imprint, or Blinkist: “TikTok for books” or “TikTok for smart people.” Headway offers swipeable book summaries with streaks and gamified challenges. Imprint presents ideas through tap-through visual slides. Users report replacing doomscrolling with these apps.

But notice what they’re doing: they’ve applied TikTok-style engagement to consumption, not skill-building. You’re not learning to speak Spanish or play piano. You’re consuming summaries of productivity books. The engagement mechanics work, but the output is passive absorption, not active skill. It’s watching workout videos instead of working out.

Nobody has applied this level of design sophistication to the hard problem: making skill acquisition feel as compelling as scrolling.

The Gamification Trap

Could you just add variable rewards to beneficial tasks? Imagine an app where you complete small work tasks, and sometimes you get a reward and sometimes you don’t, unpredictably. Would that drive motivation?

A 1999 meta-analysis by Edward Deci and colleagues examined 128 studies on this question. The finding was counterintuitive: when people expect rewards for an activity, their intrinsic motivation for that activity decreases. The effect size was substantial (d = -0.40 for performance-contingent rewards). This is the “overjustification effect,” replicated many times.

The mechanism is attribution. When you’re rewarded for doing something, you start to attribute your behavior to the reward rather than to genuine interest. “I’m doing this because I get points,” not “I’m doing this because I find it interesting.” When the rewards stop, motivation drops below where it started. The reward didn’t just fail to help; it actively undermined the original motivation.

This explains why naive gamification often produces a burst of engagement followed by a fade. Points and badges create short-term excitement, but they’re training you to care about the points, not about the activity. Once the novelty wears off, you’re left with less intrinsic motivation than you had before.

The exceptions are revealing. Unexpected rewards don’t undermine intrinsic motivation, because you can’t attribute your prior behavior to a reward you didn’t know was coming. And informational feedback (“you did really well on that”) can actually enhance motivation, because it provides genuine evidence of competence rather than external control.

This suggests variable rewards could work, but only if they’re genuinely unexpected and the tasks themselves build real skills. The moment people start expecting the rewards, the mechanism shifts from enhancement to undermining.

The Flow Alternative

Maybe the goal shouldn’t be to make learning feel like TikTok. Maybe TikTok is the wrong model entirely.

Addiction implies compulsion despite harm or lack of benefit. You keep swiping even though you’re not enjoying it, even though you have other things to do, even though you’ll feel worse afterward. Wanting without liking.

But people who genuinely love learning or working out describe something different. They’re not compelled despite lack of benefit; they find the activity itself rewarding. Wanting and liking are aligned. They might be deeply engaged, but they’re not trapped.

Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi spent decades studying this state, which he called “flow.” It occurs when three conditions are met: clear goals with immediate feedback, challenge matched to skill (hard enough to stretch you, not so hard you’re overwhelmed), and deep concentration. In flow, people lose track of time and feel intrinsically motivated to continue. Absorbing in a way that feels good, not compulsive.

The design principles for flow are different from the design principles for addiction.

First, challenge has to match skill. Too easy and you’re bored; too hard and you’re anxious. The sweet spot is where you’re stretched but capable. This is why personalized difficulty adjustment matters, and why one-size-fits-all content often fails.

Second, feedback needs to be immediate and informational: not “you earned 10 points” but “you got that right” or “here’s what you missed.” The feedback should tell you about your actual performance, not your standing in a game.

Third, real progress has to be visible. Anki does this well: you can see yourself remembering things you used to forget. Couch to 5K does this too: you can run distances that used to be impossible. The reward is the actual improvement, made salient.

Fourth, effective systems build toward production, not just consumption. Duolingo’s weakness is that it trains reception (reading, listening) but not production (speaking, writing). Real skill requires doing the thing, not just recognizing it.

Finally, based on the overjustification research, expected tangible rewards will undermine intrinsic motivation over time. If rewards are used at all, they should be unexpected, or replaced entirely by informational feedback about genuine progress.

What About Work That’s Just… Work?

Flow assumes the activity can become intrinsically rewarding. But some work is genuinely tedious: IT support, data entry, answering the same questions repeatedly. You’re not going to achieve flow while resetting someone’s password for the hundredth time. Can anything from engagement science help?

Probably yes, but not through naive gamification. Adding points and leaderboards to IT support tickets would likely produce the Duolingo pattern: short-term boost, then fade, leaving workers less motivated than before.

What might actually help borrows from TikTok without the extractive parts.

One approach is introducing variability in the task itself, not just rewards. TikTok keeps you engaged partly through unpredictability. For repetitive work, mixing task types or varying the order could break monotony. An IT support queue that surfaces an interesting edge case between routine password resets gives you something to look forward to.

Another is reframing impact. “You closed 47 tickets” is a metric. “You helped 47 people get back to their work today” is a story. Research on meaningful work suggests that connecting tasks to their human consequences increases motivation, even for routine work.

Recognition helps too, but it has to be unexpected, not scheduled. A manager who occasionally notices good work, without a predictable pattern, provides unexpected positive feedback that enhances rather than undermines motivation. The key is that it’s genuinely informational (“that was a really clear explanation”) rather than controlling (“you earned 10 recognition points”).

Autonomy matters even when the task is fixed. Control over how you approach it increases engagement. Letting IT support staff develop their own scripts, templates, or workflows gives ownership over process even when they can’t control the work itself.

And finally, there’s progress toward mastery, even in routine work. Is your average resolution time dropping? Are users rating your explanations more highly? Making this visible transforms “doing the same thing over and over” into “getting better at something.”

None of this makes tedious work feel like TikTok. But it might make it less soul-crushing, and unlike naive gamification, these approaches are less likely to backfire.

The Open Question

Could these principles produce something as compelling as TikTok for genuinely beneficial activities? We don’t fully know, because nobody has tried with TikTok-level resources. The apps that work best (Anki, Couch to 5K) are relatively simple. The apps with TikTok-level engagement (Headway, Imprint) are optimized for consumption, not skill-building.

There may be a fundamental asymmetry. Extractive apps can make the reward arbitrarily easy: just keep swiping, and sometimes something good appears. Skill-building requires actual effort, and there may be no way around that. Flow is deeply rewarding, but you have to earn it.

Still, the gap between what exists and what’s possible feels large. What would a TikTok-level engineering effort look like if aimed at genuine skill acquisition? Personalized challenge-skill matching, immediate informational feedback, visible real progress, variability without expected rewards?

We might not get “addicted to working” in the slot-machine sense. But we might get something better: work that feels meaningful and produces visible results, in ways that make you want to keep doing it. Not compulsion despite lack of benefit, but genuine engagement with genuine payoff.

The Lever

The systems are ancient. The exploitation is modern. And now you know the difference.

You can’t rewire your dopamine system. Hundreds of millions of years of evolution aren’t going to yield to good intentions. But you can design your environment so the easy behaviors are the good ones and the extractive ones require effort. You can notice the gap between wanting and liking, between the pull and the payoff.

Can the same mechanisms be redirected toward things that actually benefit you? Not simply. Naive gamification (points, badges, streaks) tends to undermine the intrinsic motivation it’s trying to enhance. Duolingo can make you addicted to using Duolingo without making you fluent in Spanish.

But there’s a different state worth aiming for. Flow isn’t addiction. In flow, wanting and liking align: you’re deeply engaged and genuinely enjoying the activity and making real progress. The conditions for flow (challenge matched to skill, immediate feedback, clear goals) are different from slot-machine engagement. Harder to engineer, but they don’t leave you empty afterward.

The question isn’t whether to engage your brain’s reward systems. They’re engaged whether you choose it or not.

The question is who’s holding the lever, and whether what it’s pointing at is worth wanting.

Sources and Further Reading

Foundational Neuroscience

- Schultz, W., Dayan, P., & Montague, P.R. (1997). “A neural substrate of prediction and reward.” Science.

- Schultz, W. (1998). “Predictive reward signal of dopamine neurons.” Journal of Neurophysiology.

- Berridge, K.C. & Robinson, T.E. (2016). “Liking, wanting, and the incentive-sensitization theory of addiction.” American Psychologist.

On Variable Reinforcement and Gambling

- Ferster, C.B. & Skinner, B.F. (1957). Schedules of Reinforcement. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Clark, L. et al. (2009). “Gambling near-misses enhance motivation to gamble and recruit win-related brain circuitry.” Neuron.

- Harrigan, K.A. (2008). “Slot Machine Structural Characteristics: Creating Near Misses Using High Award Symbol Ratios.” International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction.

On Smartphone and Social Media Effects

- Ward, A.F. et al. (2017). “Brain Drain: The Mere Presence of One’s Own Smartphone Reduces Available Cognitive Capacity.” Journal of the Association for Consumer Research.

- Dekker, C.A. & Baumgartner, S.E. (2024). “Is life brighter when your phone is not? The efficacy of a grayscale smartphone intervention.” Mobile Media & Communication.

On TikTok and Modern Platforms

- “Does TikTok Addiction exist? A qualitative study.” PMC (2024).

- Brown University. “What Makes TikTok so Addictive?”

On Treatment and Behavior Change

- “Interventions for Digital Addiction: Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses.” Journal of Medical Internet Research (2025).

Ethical Design

- Center for Humane Technology. “humanetech.com”

Comments